General characterization of gravity currents

A lock-exchanging procedure occurs when the denser fluid flows in one direction along the bottom of the system whilst the lighter one flows in the opposite direction along the top boundary (Fig. 1). This phenomenon occurs due to the difference in the hydrostatic pressure (heavier fluid stays in the bottom, whilst lighter fluid goes up). The current speed is controlled essentially by the ratio of the flow inertia to the gravitational force (density difference and boundaries conditions).

Gravity currents occur in many natural situations, such as cold fronts, avalanches, river-lake systems (Ishikawa et al., 2021; River Res Appl .), among others. To describe the dynamic of gravity current usually we use the dimensionless bulk Froude number (Birman et al., 2007; Phys. Fluids):

\[Fr = \frac{u^2}{g'~h}\]

where Fr is the Froude number, u is the front speed, g' is the reduced gravity, and h is the height of the gravity current (from the head or from initial height, which depends on the theoretical framework used and the situation that we wish to model).

Assuming that the flow is governed completely by Benjamin's energy-conserving theory (there is no energy loss due to mixing or viscous dissipation), the Fr = 0.5 (Benjamin, 1968; J. Fluid Mech.).

In spite of gravity current is often observed in natural situations, many studies have been conducted in laboratories tank to highlight the main aspects that could not be revealed in field observations.

We can note that Benjamin's energy-conserving theory is not valid in many situations, even in simple conditions. Laboratory investigations have shown that due to the friction of the tank bed, the heavier current propagates slower than the upper one (Shin et al., 2004; J. Fluid Mech.).

Moreover, the formation of Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities due to the shear between two-layer exchange flow is often observed during the propagation of gravity current (Fig.1), favoring the dissipation of energy and mixing.

In this example, the fluid mixing takes place by Kelvin-Helmholtz rolls stirring toward smaller scales (Simpson, 1986; Acta Mech.). Initially, three vertical eddies are formed, however, two of them break due to mutual interaction. In the simulation, we may also observe that KH billows favor the mixing processes between both fluids.

The mixing extracts energy from the current, reducing the density gradient, and may also influence the speed of the flow since Fr is also a function of the density difference.

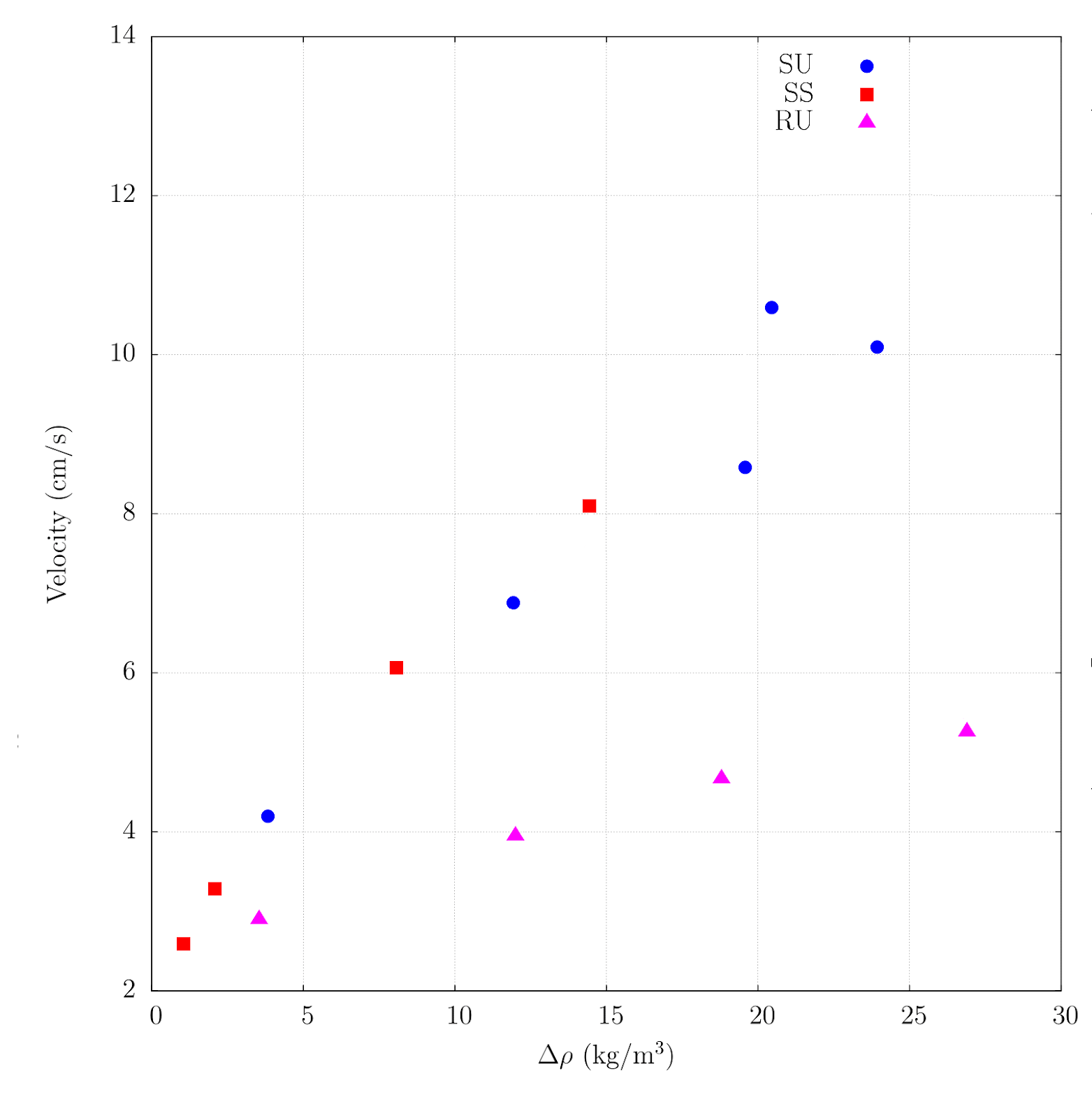

Gravity currents have been studied for different environment configurations. We generated gravity current in a smooth bed, varying the density difference. As expected we observed that as higher is the density difference, the higher is the velocity of the gravity current. We compared the dynamic of these gravity currents through gravity current excited in a rough bed formed by continuous spherical elements (Fig.2)

We observed that the roughness elements have a higher impact on the average velocity and mixing when the density difference between the current and the ambient increases (Fig.3).

For a small density difference (Δρ ≅ 3.0 kg/m3), the system was practically unperturbed by the elements, following exactly the same energy-conserving behavior as observed in smooth bed experiments.

A practical application of this result may suggest that due to the small density difference of gravity current in lakes and reservoirs (river intrusion), gravity current in lakes and reservoirs may not be strongly influenced by the roughness of the lake bed, and could be compared to propagation in a smooth bed condition.

We also investigated the evolution of gravity current in a two-layer media (a typical situation observed in the majority of lakes and atmosphere). We observed that the velocity is slightly modified when the gravity current is flowing within a two-layer stratified system and interfacial waves may be generated in front of the gravity current depending on the stratification condition (low-density difference between lower ambient and the gravity current).

We suggested that solitary interfacial waves that just propagate in front of the gravity current extract energy from the system leading to a constant deceleration of the gravity current. However, results also suggest that during some conditions (often due to higher stratification conditions between current and ambient), internal waves are not generated, gravity current propagates with a similar velocity of smooth bed (de Carvalho Bueno et al., 2018; 38th IAHR World Congress).

Although we observed an influence on the propagation of gravity current speed, we did not observe an additional mixing caused by the presence of interfacial waves. We suggested that additional mixing just should occur on interfacial wave shoaling, which was not investigated in this study (de Carvalho Bueno et al., 2018; 38th IAHR World Congress).

Since gravity current is often observed in many natural systems and has kinetic energy that may favor the horizontal and vertical transport of sediment, we also investigated the horizontal transport of sediment and sediment resuspension caused by the propagation of gravity currents. We are analyzing the mixing efficiency and sediment resuspension through laboratory experiments. First, the aim of these pair of studies were only to create a software capable to investigate the dyanmic of sediment induced by gravity current, mainly for educational purposes (Silva et al., 2021; XXIV SBRH).